Nightshift Studios

|

Nightshift Studios |

|

First Name · · Last Name

Last Name · · Groups

Groups · · Venues

Venues · · Events

Events · · Entities

Entities · · Submit

Submit · · e-Mail

e-Mail · · Links

Links · · Search

Search |

|

|

Arnie van Bussel Collection |

Nightshift Recording Studios |

|

|

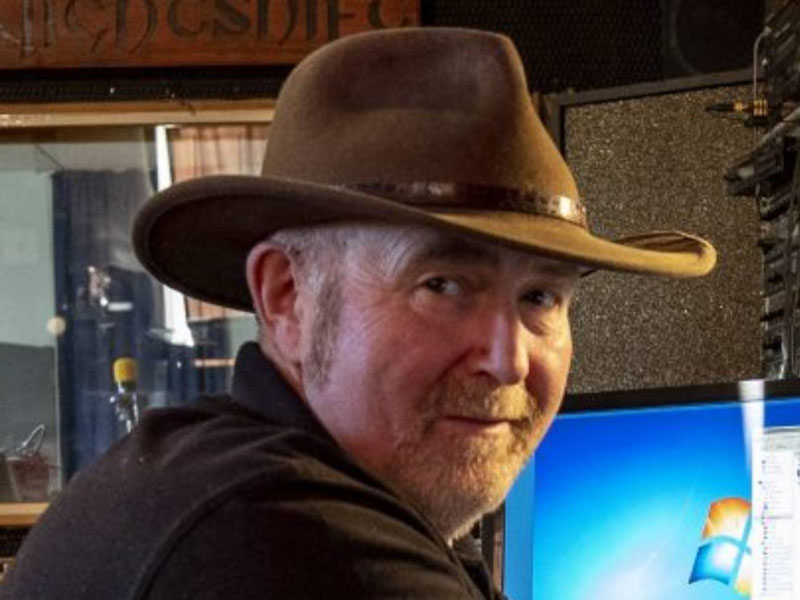

As he has for some years, he worries that our nation's musicians are not getting enough support. Many of our household names struggle financially, the majority have other jobs to support their creative pursuits. "It's always been tough," he says. ; "But now it is really tough." He's at retirement age now, he confides, easing back into a chair in front of a one-off recording console which he's used to capture the sound of Christchurch for more than 40 years. Times and recording methods have changed and the enormous console's function is different now, but he is still using it to record everything from folk songs to death metal. Now he uses modern recording methods too. ; He's stitching together the past and the present in sound. But don't get any ideas about him having a fancy studio. "There's nothing flash about this place," he says, waving an arm about him loosely. ; A denim-clad leg circles the base of his chair. "That's deliberate. ; If this place was too swish no-one would relax and I wouldn't get a good sound out of them." As if to illustrate his point, a lengthy train carrying coal shudders past so close I feel I could stick my arm out a window and be within cooee of actually touching it. Without blinking he continues talking. ; He says the rumbles of trains don't affect his recording schedule. |

' ' |

' ' |

' ' |

' ' |

Before we arrived at his Nightshift Studio, which is a separate building at the rear of his home in Woolston, Christchurch, van Bussel had carefully etched a crack along an outside wall with an index finger. "Earthquake did a bit of damage," he says in typical understated fashion, his eyes trailing across the lawn to the scaffolding at the rear of his home which is still undergoing repairs eight years after the 2011 earthquake. There's a sense that van Bussel has always been determined to continue in his chosen vocation despite all obstacles. Shaking his head, he taps a keyboard and a screen jolts to life. "Christchurch has so much talent, so many people making truly great music, but despite the advances of the internet most of them will never be heard because of where we are in the world." In the 70s, the A+ student found himself being steered towards an engineering degree at Canterbury University while playing in the mainstream rock band Flood on the weekends. Soon the long-hair found himself gazing wistfully into the art rooms instead. He started out recording his friends' bands and learnt as he went. "Word quickly spread that I was doing it, more people asked me. ; There were three professional recording studios in Christchurch in those days," says van Bussel. ; "But I didn't cost much." Now you "can't walk down the street without bumping into a recording studio". |

' ' |

The Dance Exponents recorded their first demo of the New Zealand classic Victoria with van Bussel. "I still have it in my archives," he says. ; "In those days the songs were recorded in Christchurch and all the mastering was done at EMI in Wellington. ; I took the tapes up and had a look around for myself, which was interesting." "We first encountered Arnie because we are doing demo recordings, we are not signed to anybody at this stage, we are wondering what we sound like and do de do. ; We thought we might be able to play these to record company people," says Luck, on the phone from Gisborne. "Then we do get signed by Mike Chunn, he didn't hear any of the demos, he just saw us live. ; He mentioned about recording Victoria with a string arrangement so we got Peter Cooke and Richie Hlavac from The Wastrels and they did the string section. ; We go into Arnie's with Roland and Arnie's as generous as ever and we record a demo. At the time one of the reasons we went there was his good reputation, Arnie was super helpful and The Bats had recorded their first EP there and that impressed us no end as well." A lot of studios could be sterile, posh, says Luck, which was why van Bussel's studio appealed. "His studio was homely and friendly, no restrictions, you could do anything in there. He did everything live. We used Nightshift when we were no longer in Christchurch. ; The Only I Could Die demo was done there, such was Arnie's high recording standards and price." In the 1980s record store manager Roger Shepherd founded the fledgling Flying Nun label in Christchurch. As a whole, for many the label's signature lo-fi sound came to represent the isolation of the South Island and New Zealand. Largely Flying Nun emerged from austerity, run on the smell of a beer-spilled coaster following the large-scale hacking and deregulation of the early 1980s. Dunedin was the label's spiritual home and fostered such important New Zealand bands as The Verlaines, The Chills, The Clean and Sneaky Feelings. But Flying Nun had its creative roots in Christchurch. The first single released off the label was the Pin Group's seven-inch Ambivalence/Columbia, closely followed by Tally Ho by The Clean, which reached No 19 in the New Zealand singles charts. In the early days, bands would record at eight-track studios like Nightshift, make their own artwork and posters and then deliver the tape to the label's Christchurch office, where either Shepherd or The Clean's drummer, Hamish Kilgour, would distribute it. Kilgour once told me about the first time he met label founder, Shepherd. "The Enemy had come up from Dunedin to play, so they brought The Clean up, too. We were diabolical. We arrived in a state of disarray and did a shocking gig. Afterwards, Roger Shepherd travelled home on the bonnet of the car. This strange person was sitting like a gargoyle on the front of the stationwagon. I asked someone who he was and they said, 'That's Roger Shepherd, the manager of the record label'." Kilgour says Tally Ho cost $50 to make. He doesn't want to quibble but van Bussel thinks it was actually $48. "It was done using cheap mics, very quickly one evening," says van Bussel. "I charged $10 an hour." Back then there were no courses in how to do studio recording. "Anyway, I was learning by making mistakes. It was all done on a shoestring ... ; I recorded Mainly Spaniards, Playthings. ; I was in a mainstream rock band and recording these Flying Nun guys and people that wanted to create that lo-fi sound." From New York this week, Kilgour says he remembers the "unique" recording session. "Arnie was a very casual and easygoing guy to work with who run his drum tracks through a guitar pedal for a unique drum sound ... this later changed. I did only two sessions with him, The Clean's Tally Ho and a Strangeloves single." Afterwards, van Bussel says there was a "bit of a problem". "It was recorded on half-inch tape. The Clean wanted the tape but they were costly things and people had to pay me if they wanted the tape back, I couldn't afford to buy many so I'd wait a while and then would recycle the tape. I always tried to give the bands a lot of time before I did that but sometimes they didn't take the opportunity. I gave them two years, they didn't get it so I recycled it ... they were quite upset at the time. It was grassroots stuff, I couldn't afford to do anything else." He smiles and taps the side of his nose. "There might be a documentary or two in the wings," he says mysteriously. "I've been maligned a bit over the years about that tape but it might be about to change. |

' ' |

' ' |

' ' |

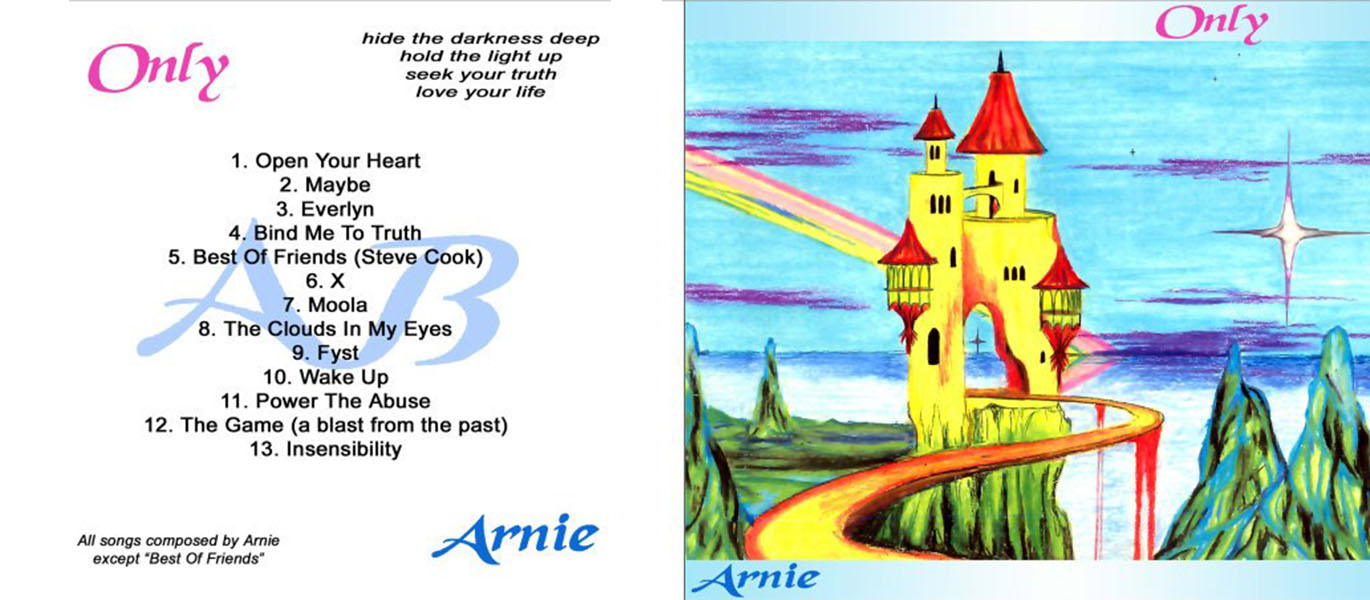

Initially, Flying Nun concentrated on recording Christchurch bands, namely the Pin Group's EP, records by Bill Direen's Bilders, a single by all-female band 25 Cents and The Bats. Robert Scott, of both The Clean and The Bats, fondly recalls working with van Bussel. "He was a big bearded Dutchman, full of life," says Scott. "The first time was recording Tally Ho with The Clean. We all played at the same time, me on bass, then showed Martin Phillipps the keyboard part and he chucked that on. Next time would have been doing the By Night EP with The Bats ... We developed a good understanding over the next few recordings, Music For the Fireside, Daddy's Highway, Couch Master, to name a few, each time was like coming back to a familiar place, a good feeling. "These days musicians send him their digital arrangements and he turns them into songs. "It used to be that a recording studio was a special place, but with the changes in technology everyone can have a recording studio in their bedroom now," he says. "It is all very well having the gear, but if you don't know what you're doing or the knowledge, it still isn't going to sound as good as it could," he says. ; "Not everyone is Lorde. ; Another problem we are starting to face now as professionals is that so much of the technology is being designed for use on small devices like phones." After four decades in the music industry, he believes a recording engineer's main attributes lie in people skills. There's an art to making people trust you to interpret their creative idea and make it tangible. "You can be good with bells and whistles but if you're not good with people it just won't work." In 40 years, noise control has visited his studios only once. It's something he's clearly proud of. "I let a young band borrow the studio for rehearsal while I was away," he recalls. "But it was a stinking hot day so they opened the windows and doors and the sound carried right across the neighbourhood. But I reckon one time in 40 years isn't bad." He's a pensioner now. He's seen music fashions come and go. In the 90s he "nearly died" but his love of music sustained him. "I was really sick, wasting away ... I found out eventually that I had coeliac's disease but I was unable to do anything for two years. I still had my recording gear so bit by bit I got by doing that while I recovered .... it saved me." Handing me one of his CDs, van Bussel adjusts his Stetson hat and turns up a song he's been working on with Christchurch musician Phil Doublet. "He's a prolific multi-instrumentalist but this particular song has massive commercial potential. If someone in the US could hear this and market it, this would sell millions. Sadly, the likelihood of them hearing it is small," says van Bussel. "This is what our musicians face. You can have the talent but with online there's so much noise now, it's harder than ever for them to be heard." Luck describes van Bussel as "an inspiration" to many in New Zealand music. "He is someone who has supported musicians behind the scenes for many decades." For van Bussel it's about being lucky enough to spend his life on something he loves. "They say that, don't they, find your passion and the rest follows ... I found music and I'm still following." |